This report from the field by Pure Earth program officer Lavanya Nambiar shares updates about how our work is improving lives in a village in Bangladesh .

In Mirzapur, a small village on the outskirts of Bangladesh’s capital city, Dhaka, villagers like Shaila Akhtar complained of smoke and stench, and a thick layer of dust, which they later learned was toxic lead, settling in and around the area, making the village almost unlivable.

During an environmental assessment in November 2018, investigators from Pure Earth’s Toxic Site Identification Program (TSIP) found active recycling of used lead-acid batteries happening right next to the village, exposing an estimated 255 children, including Shaila’s two sons–Saim and Shihab–to toxic lead. The informal recycling operations had been polluting the village for over 3 years.

At informal recycling sites, used lead-acid batteries are manually dismantled and lead is smelted in open pits, with no environmental controls. Consequently, lead spreads and lands on surrounding soil and vegetation. These operations also leave behind large quantities of battery waste–like plastic casings and separators–which contain high levels of lead.

Lead exposure causes irreversible damage, particularly to children’s brain development. Children in the community frequented the recycling sites, often with bare feet, unaware of the dangers and the impact the lead dust could have on their brains and their future.

Given the gravity of the situation, the project team knew that a successful and effective risk-mitigation project was urgently required to reduce the adverse environmental and human impact in Mirzapur.

In 2019, following pressure from the community and the government, the smelting operations ceased in the area. Pure Earth, with the University of Dhaka and the environmental engineering firm TAUW, decided to conduct a more detailed assessment of the site to better understand the extent of the pollution and the remediation options.

Soil surrounding the former smelting operations was found to have levels of lead exceeding international guidance levels for residential areas by as much as 50 times.

The contamination covered an area of approximately 4.5 hectares.

Shaila’s story: One of many in Mirzapur

During her interview with the Pure Earth team, Shaila described how the battery breaking and smelting operations made her family’s life miserable. The stench from smelting at night made it hard to breathe, and a heavy coat of lead dust settled all over their homegrown vegetables.

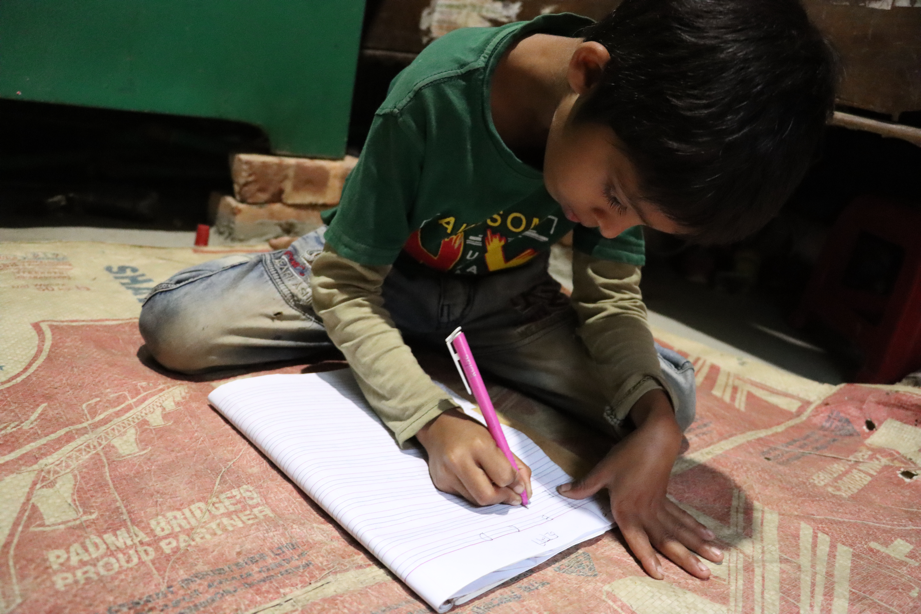

Shaila reported that her son Saim, who used to do well in school, had gradually started forgetting his studies. Suspicions over the role of lead in Saim’s struggles were confirmed through a blood test, which showed that Saim had extremely high levels of lead.

Time For Action

Lead will remain in the environment without intervention. It is thus critical to remove the source of lead as quickly as possible to prevent further exposure to residents, and also to prevent future generations of children from suffering the same fate,

In their effort to identify and select the most appropriate and effective actions, the team considered many factors, including the extent to which the intervention would reduce risk to public health, the sustainability of the intervention, community and government acceptance, the timeframe and cost, and the logistical feasibility in a rural, low resource area.

The remediation

The remediation was carried out in the following manner:

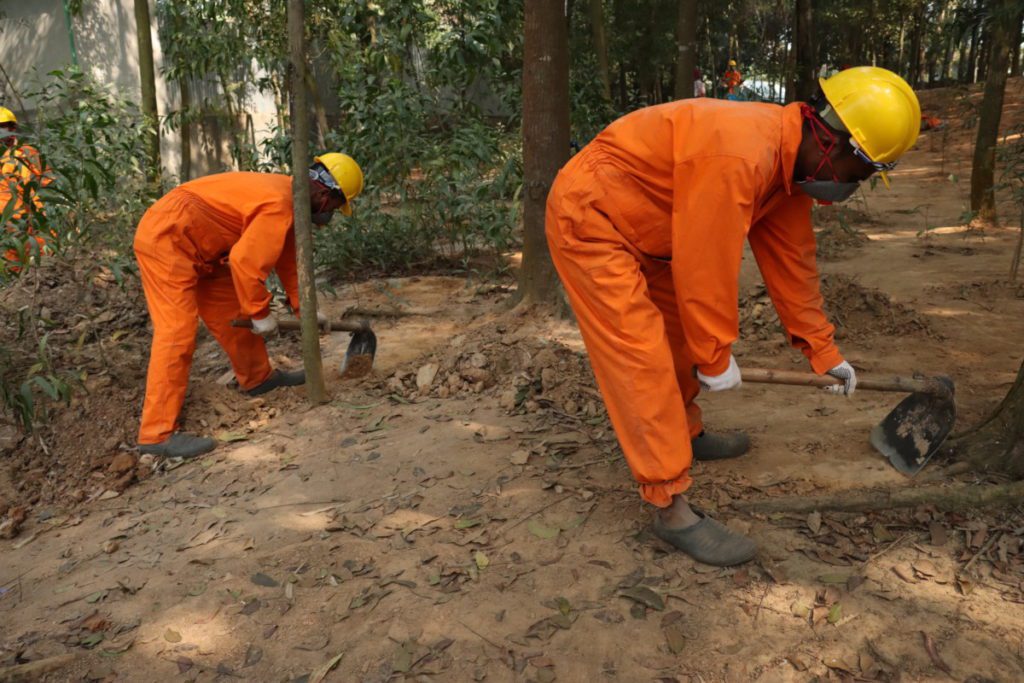

- The contaminated surface soil and leaves were scraped or excavated, and consolidated into specific areas.

- Lead contaminated soil was removed from the smelting area, community grounds, and residential yards.

- Two pits were dug to create an area to safely dispose of the contaminated material.

- The contaminated soil and leaves were mixed with phosphate to reduce the bioavailability and leachability of the lead before being buried. Concrete from the smelting area was broken up and incorporated into the pit.

- A geotextile layer was placed over the pits and a meter of clean soil was placed on top of that as a cap.

- Clean soil was placed down across the excavated and scraped areas.

- The battery waste was collected and disposed of at an established landfill away from the village.

- The homes in the community were thoroughly cleaned to remove any remaining lead dust.

Engaging the community

Beyond the remediation, Pure Earth engaged extensively with the community and local leaders in Mirzapur prior to and during the project to receive their input on the planned activities.

A community event was organized by Pure Earth and the University of Dhaka with support from UNICEF and local NGO icddr,b aimed at raising awareness about lead pollution, sources of lead exposure and its impact of human health and environment.

Community members actively participated in the event, and shared their experiences of being impacted by the once-active battery recycling operations. Posters, pamphlets, and social media posts were also developed to spread the word.

Led by Pure Earth’s partner, icddr,b, blood lead levels of children in Mirzapur were collected before the start of the remediation. Icddr,b also collected the same data from children in comparison communities to better understand risk factors.

Building A Model

The Mirzapur remediation project was important not just to alleviate the environmental and health impacts of lead but also to serve as a proof-of-concept for the government of Bangladesh, and for any other group interested in practical, low-cost steps to reduce health risks from lead.

Pure Earth has identified more than 250 sites affected by used lead-acid battery recycling in Bangladesh, and the World Bank estimates there are as many as 1,100 sites across the country. If left unchanged, such sites will continue to poison future generations of children. Future remediations such as the one carried out at Mirzapur can be initiated and implemented with in-country expertise.

Therefore, a series of meetings, seminars, and discussion sessions were organized with the Department of Environment (DoE) and other relevant stakeholders at which Pure Earth presented the Mirzapur lead remediation strategy and advocated adopting this replicable approach throughout the country.

Assessing health impacts

By the completion of the cleanup in May 2022, soil levels in Mirzapur were safely below the international standards. But the true confirmation of the success of this project will come in mid-2023. At that time, the children whose blood lead levels were assessed before the remediation will re-tested. Only then will we know how much the cleanup has impacted Shaila’s sons and the other children in Mirzapur. But we know the cleanup is already protecting future children yet to come in the community.

—

This project was made possible by the generous support of the Tauw Foundation, USAID, and the Clarios Foundation.

Learn More

Watch local news coverage of Pure Earth’s work in Bangladesh.

Learn more about how lead has impacted Shaila’s family.

https://youtu.be/6NNvM5T0IVo